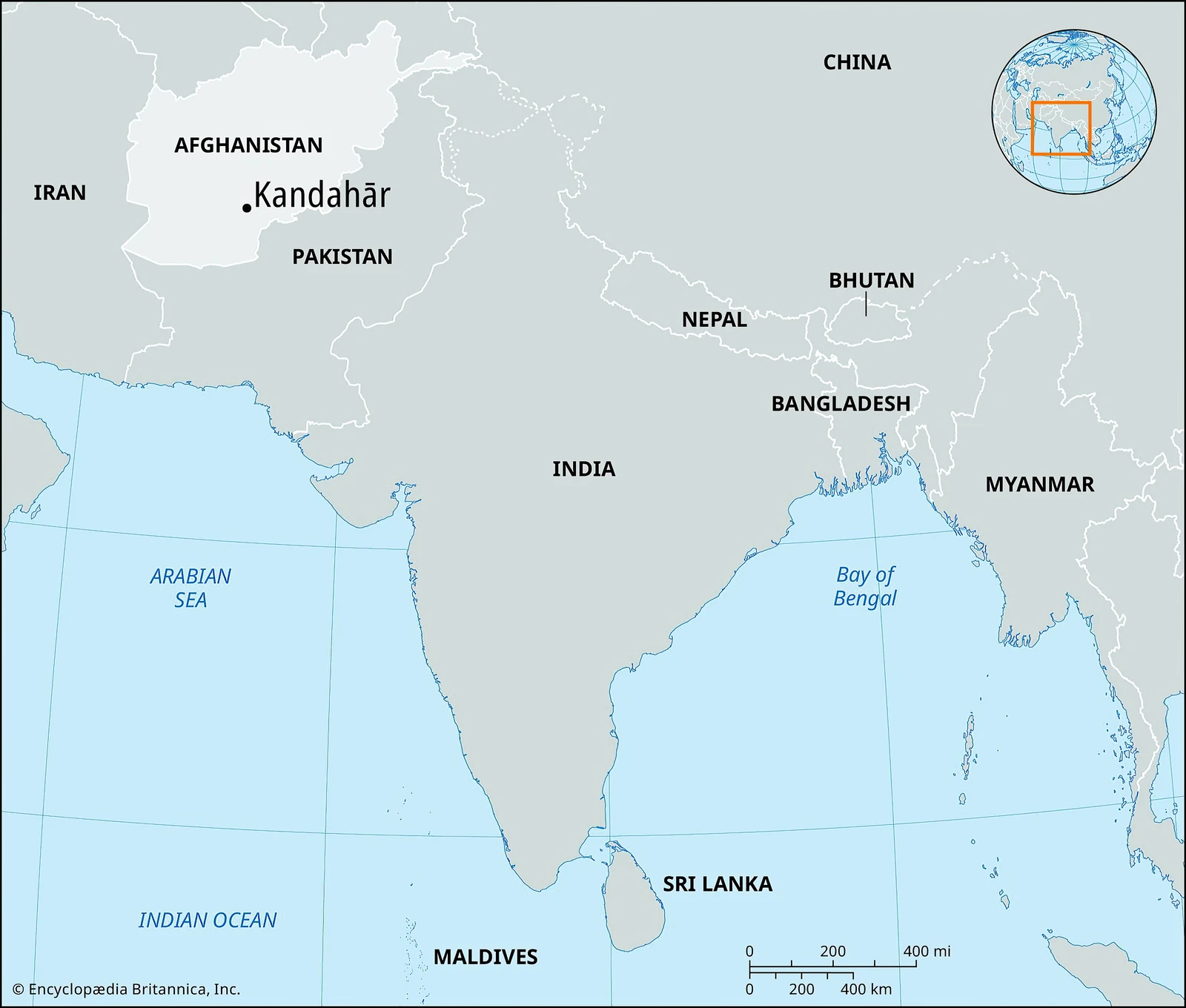

Old Kandahar City Ruins, locally known as Zorr Shaar, are the historical remains of the ancient city of Kandahar in southern Afghanistan. This archaeological site is a profound testament to millennia of urban life, situated at a crucial crossroads of ancient trade routes, and is a living chronicle of the rise and fall of countless empires.

Listen to an introduction about Old Kandahar City Ruins

Name: Old Kandahar City Ruins (Pashto: زوړ ښار, Zorr Shaar, lit. “Old City”; also Shahr-i-Kona, meaning “Old City,” or Alexandria Arachosia in its Greek period)

Address: The ruins are located on a hill and the surrounding plain, a few kilometers west of the modern city of Kandahar, in southern Afghanistan. They are strategically positioned near the Arghandab River valley.

How to Get There:

Travel to Kandahar is currently extremely difficult and unsafe for general tourism due to the political instability in Afghanistan. The following information is for historical context and is not a recommendation for travel.

- By Air: The closest airport is Kandahar International Airport (KDH).

- By Road: Kandahar is a major city in southern Afghanistan, connected by road to other parts of the country, though travel can be dangerous.

- Within the City: The ruins are located on the outskirts of the modern city. In more stable times, a taxi or local transport would be used to reach the site.

- Entrance Fee: Prior to recent events, there was a nominal entrance fee for the site.

- Best Time to Visit: The cooler, dry months (October to March) are ideal.

Landscape and Architecture:

The “architecture” of Old Kandahar is an archaeological tapestry, revealing layers of urban and military structures from different historical periods, often built of mud-brick and clay.

- Layered Urban History: The site is a complex of successive cities built one on top of the other, with archaeological evidence of occupation dating back to the Iron Age (1st millennium BC) and possibly earlier. The city was founded in its prominent form in 330 BCE by Alexander the Great, who named it Alexandria Arachosia. It later fell under the rule of the Mauryan Empire (under Ashoka), and subsequently the Greco-Bactrians, Parthians, Kushans, Sassanians, and many others, each leaving their mark on the city’s architecture and layout.

- Citadel: The ruins include a prominent citadel on a hilltop, which served as the seat of power and a fortified area for centuries. This citadel was fortified with high, strong walls of packed clay or mud-brick, with moats and towers. It was rebuilt and expanded by various rulers, including the Mughals. Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan is recorded as having extensively repaired the fort. The remains of a royal residence can still be seen at the top of the fortified citadel.

- Defensive Walls and Moats: The city was historically surrounded by massive mud-brick fortification walls and a moat, which protected it from invasions and sandstorms. Although much of the wall has eroded or been dismantled over time, its original extent is still visible.

- Chihil Zina (Forty Steps): On the northern side of the old citadel, there is a famous rock-cut monument known as the Chilzina (or Chehel Zina), which means “Forty Steps” in Persian. This is a chamber carved out of solid limestone with a staircase of 40 giant steps leading up to it. It was commissioned by the Mughal Emperor Babur in 1507 to record details of his conquests and his empire. It provides a commanding view of the surrounding plains.

- Religious and Secular Structures: Archaeological excavations have revealed remnants of various other structures, including:

- Mosques: Evidence of mosques and Islamic-era buildings exists, reflecting the city’s conversion to Islam in the 7th-9th centuries.

- Buddhist Complexes: A Buddhist complex was built on a spur of the Qaitul ridge, overlooking the city, during the 3rd century AD.

- Hindu/Zoroastrian Temple: Historians also mention the existence of a fire-worshipping temple in the city’s early history.

- Water Storage: The remains of water storage ponds and irrigation systems, essential for survival in the region, are also evident.

- Destroyed and Abandoned: The city was sacked and plundered multiple times throughout its history, most notably by the Mongol invader Genghis Khan in the 13th century and completely destroyed by the Persian conqueror Nader Shah in 1738. The city was abandoned after this event, and a new city was built nearby by Ahmad Shah Durrani, the founder of modern Afghanistan.

What Makes It Famous:

- Strategic Crossroads of Empires: Old Kandahar is famous for its strategic and commercial importance as a crossroads of major trade and invasion routes, linking India, Persia, Central Asia, and Mesopotamia. Its long history of conquests and constant rebuilding is a direct result of this geographical significance.

- City of Alexander the Great and Ashoka: The ruins are historically significant as the site of Alexandria Arachosia, a city founded by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, and later an important outpost of the Indian Mauryan Empire, which was ruled by Emperor Ashoka. The discovery of Greek and Aramaic inscriptions by Ashoka provides definitive historical proof of this connection.

- Archaeological Layers of a Long History: The site provides an invaluable record of Afghanistan’s long and complex history, from the Iron Age, through the Hellenistic, Mauryan, Kushan, Sassanian, and Islamic periods, all within a single archaeological area.

- Chilzina (Forty Steps): The rock-cut steps and inscriptions by the Mughal Emperor Babur are a significant historical landmark within the ruins, a testament to the city’s importance to successive empires.

- Symbol of Historical Resilience: Despite being destroyed and abandoned, the site stands as a powerful symbol of the resilience of Afghan heritage and the city’s enduring role as a center of power in the region.

Differences from Some Other Wonders:

- Multiple Cities on One Site: Unlike ancient sites like Mohenjo-daro or Harappa, which represent a single civilization’s urban planning, Old Kandahar is a palimpsest of multiple cities and civilizations built over thousands of years (from ancient Iron Age to the 18th century), each with its own distinct architectural style and layout. This long, continuous, and layered history is a key differentiator.

- Evidence of Greek and Indian Rule: The discovery of Greek and Aramaic inscriptions of Emperor Ashoka is a unique and famous feature, providing definitive evidence of the city’s connection to both the Hellenistic and Indian Mauryan empires, a confluence of cultures that is central to its identity.

- Predominantly Mud-Brick and Clay Construction: While some monuments in the region are stone (Takht-i-Bahi), the primary material for the massive walls and many structures of Old Kandahar was mud-brick and packed clay, reflecting local building practices and a different type of construction than the monumental stone of Angkor Wat or the baked brick of Mohenjo-daro.

- City of Ruin vs. Conserved City: While some ancient cities like AlUla Old Town have been recently abandoned and are now being restored, Old Kandahar’s ruins reflect a more complete historical destruction and abandonment in the 18th century, with the modern city of Kandahar built elsewhere, giving it a different character as a truly lost city of ruin.

- Less Focus on a Single Monument: While the Chilzina is a key highlight, the “wonder” of Old Kandahar is not a single, dominant monument (like the Qutub Minar or Minaret of Jam), but the entire archaeological landscape of a lost city that holds thousands of years of history.

- Historical and Political Context: Its identity is deeply intertwined with its role in the long history of conflicts between the Safavid and Mughal empires, and its final destruction by Nader Shah in 1738, a dramatic narrative that is central to its fame.